There are several parallel conversations going on in

Business English training at the moment. The first is about money. The second is about qualifications. The third is materials. There are certainly other issues, but I’ll

limit it to these today.

The purpose of this article is to link these three threads

and to give a few signposts out of the circular debate. The link to all of these lies in business

theory. As Business English trainers, I

hope this is familiar, but perhaps the application to our own field is new.

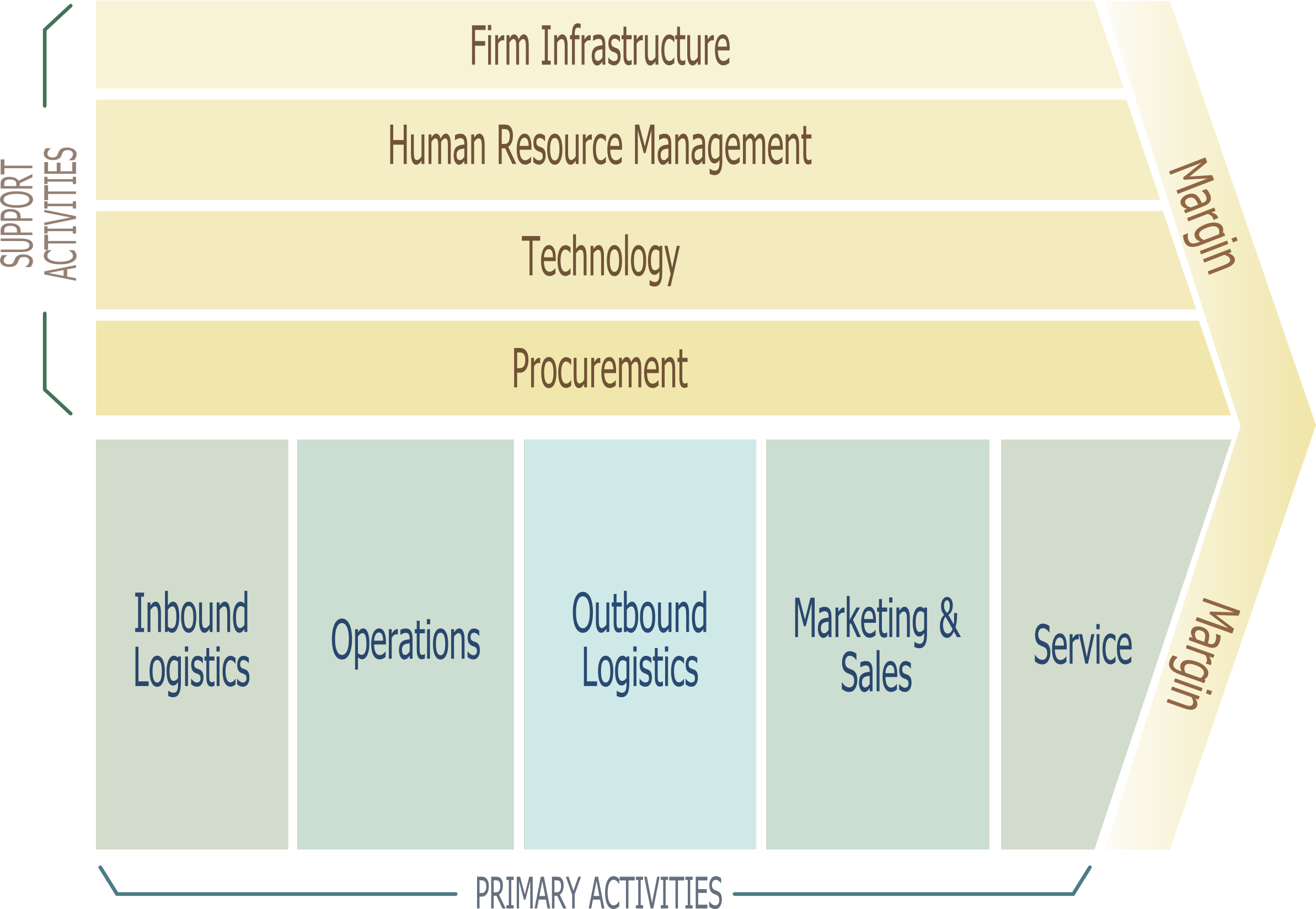

Porter’s Value Chain

Perhaps the most well-known name in business theory is

Michael Porter. In 1985, he presented

the value chain, which explains the difference in price between the inputs and output of a

business.

I think the clearest graphic of this process is from Wikipedia which

shows a notional value chain for a manufacturer.

The business functions in blue are the primary functions of

the business in transforming the raw materials into a product and selling that

product to generate profits. The

functions labeled in brown support those primary activities and generally do

not add value in themselves. These are

also typically the first business functions to be outsourced. The difference between the cost of running

these activities and the final price is the profit margin. Each firm will have a different value chain,

but all will resemble this model.

The Value Chain for

Business English Training

Now, let’s take this model and apply it to Business English

training.

The raw material of BE is the English language, which is a

common good. It belongs to no one and if

you grew up in a native-speaking country you have it free-of-charge. Indeed, there are enough resources and

materials on the Internet that the language is available at no charge around

the world. Therefore, the main value of

the trainer is to determine which parts of this massive body of knowledge are

needed, organize that information, then transform it into a useful format for

learning, mastery, and performance.

Overall, the first three activities are determining what

to train, and the last two are how to train. These primary activities include everything

in training from using discourse analysis to determine key functions to

elearning. Additionally, materials

development includes more than simply course books and handouts, but also the

activities a trainer uses to instill knowledge, mastery, and performance.

Note: It can be argued

that marketing actually adds value but I doubt few trainers will be able to

develop a brand with enough mass to considerably change what a client is

willing to pay. For simplicity I have

left it as a supporting activity.

Why wages are so

low...

Jenny has a CELTA and works at a private language

school. She is given Business English

courses and travels to an accountancy for a 90 minute lesson every week. The school and the client have decided to use

a course book for the training. Jenny supplements

the material with some of her own activities and modifies some of the exercises

in the book to better fit the needs of the group. She conducted a short needs assessment at the

beginning to find out which parts of the book are more important for the

learners. She is not that familiar with

the company but she has read the company’s website and remembers some accounting from a

university class she took several years ago.

She is very active reading blogs and articles to find creative lesson

plans and activities to improve her teaching.

In the case above, Jenny is only one very small part of the

value chain (marked in red). The other

primary activities were done by the course book writers/publisher (they were

paid when the book was bought) and the brown support activities were done by

the school.

Let's imagine the market price for this type of training is €60

per hour. If Jenny gets a third of that,

she is lucky. Her limited needs

assessment is added value and her addition of supplementary materials

helps. Most likely, she will receive a

bit more than her peers at the school who do not do this. But her professional development is limited

to improving her training delivery. This

is admirable, but does nothing to increase her wages. She is already receiving this portion of the

value chain.

Susan has a CELTA and is a freelance trainer. She started with general Business English

courses but then started focusing on finance.

Every two weeks, she attends a local networking event for business

leaders in the area. At one event she

meets a partner of one of the local accounting firms. She talks about her business a little and how

she has worked with other firms in the field and has seen good results. She has developed a corpus of financial

English and writes her own materials based on common functions and skills. Prior to the training, she researches the

firm and meets with a few of the partners to conduct a top-down needs

assessment. Then she conducts a

bottom-up needs analysis with the participants.

She designs a course proposal and negotiates with the accountancy. She then develops the materials and conducts

the training. Every month she invoices

the firm and sends a progress report to the partners every quarter.

Again for simplicity, let’s assume that Susan is also subject to

the same market rate for Business English training at €60 per hour. But in this case, Susan collects every cent

of the value chain. Additionally, she is

developing skills and tools which enhance her ability in other activities. Over time, she becomes more proficient at

billing, reporting, marketing and sales.

She checks on activities and methodology but is more interested in

workplace discourse, specific needs in the field of finance, etc. So, she does not ignore how she

teaches, but spends an equal amount of time on what she teaches.

In the next chapter we will discuss the relationship between qualifications and the value chain to see how hitting the books will help increase wages.

.png)