As some of you may know, I was in the US Army before I was an English trainer. As a Sapper (combat engineer) my life was consumed by the neverending cycle of training-execution-training. During my seven years in the military and three years in combat, I rose to the position of platoon sergeant, including designing several company training programs in insurgent tactics and dealing with improvised explosive devices. I was passionate about training and adopted the military's models and processes whole-heartedly.

|

| Your author doing a little training... note, I had to swim back, too. |

However, after my CELTA and beginning in the BE field, I seemed to forget much of what I had learned and practiced during my previous career. It wasn't until about a year ago that I sat down and took stock of my military experience and how it applied to my new passion. In the end, I distilled five points which apply to in-company training.

1. The Mission Essential Task List (METL)

A METL is a list of key tasks a unit must be able to successfully accomplish in order to fulfill their mission. For example, when I entered the Army in 2002, we were still trained in the 1980-90s conventional warfare skills. In that situation, a combat engineer platoon must be able to emplace a standard NATO minefield. This essential task supported the company's METL to emplace a battional defense. Below platoon, a squad had a list of essential supporting tasks for the minefield. Below that, each individual soldier had to master a list of key tasks (such as arm a mine) for the whole unit to be successful.

As an English trainer, this shows us two things. First, our learners do not exist in communication isolation. They belong to teams, departments, and business units. The individual skills we teach them are part of a larger goal. It is helpful for us to consider how we are supporting these goals. Second, the key skills needed by the learners are mostly determined by their position within the structure. In English training, the most generic METL is the ALTE can do statements. These are particularly valuable for pre-experienced learners just as the individual soldier task list drives the basic training program in the Army. However, once we are in-company, a key part of pertinent training is defining the essential skills for the learners, their teams, and their departments.

2. Task, Condition, Standard (TCS)

To evaulate performance, every task needed is outlined using the task, condition, standard format. Basically, the task is restating what the learner should be able to do. The condition outlines the environment in which they are expected to perform the task. And finally the standard is a 'checklist' of performance steps for them to correctly execute.

For example, here are the standards for throwing a hand grenade:

|

| FM 3-23.30 Grenades and Pyrotechnic Signals, Dept. of the Army, approved for public release |

Back to English teaching, this sounds like something we should be doing with our skills training. Yet measuring can do statements in this way is not universal. Oxford University Press and John Hughes have taken a step in this direction with their skills assessment criteria in the Teacher Book from Business Result. However, I would like to see more of this in 'opening a meeting', 'making arrangements on the telephone', etc. For myself, I have set the task of writing out some of these performance steps and the conditions under which they must be performed (e.g. in a conference room with projector and presentation). Perhaps we need to borrow something from our academic colleagues on this one... they are the experts at assessment.

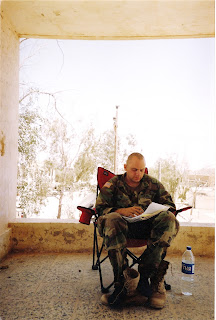

|

| Writing a letter home in 2003 near Hit, Iraq |

3. Crawl-Walk-Run

Once each needed skill is defined in the METL and the TCSs are set, the military trains to proficiency using the crawl, walk, run approach. Under this approach, the task and the standards are kept the same, but the conditions are changed. This means increasing speed, spontaneity, complexity, and realism.

|

| From FM 7-1 Battle Focused Training, Dept. of the Army, approved for public release |

Note, the performance steps remain the same, only the situation becomes more difficult. For example, in a presentation setting, this could mean that questions from the audience become more difficult, speakers could have non-native accents, etc.

In general, I try to incorporate this into my training. So, when the learners become confident that they can participate in a meeting, I start adding more challenging elements. For example, I will add in listening with Asian accents, add the element of interruptions and unclear vocabulary, place the meeting under pressure constraints such as time or consensus, reduce/remove prep time, add an additional skill like note taking, etc. This helps build the difficulty.

4. Train as you fight, fight as you train

This all adds up to the next lesson. In the military the goal (especially in the run phase) is to make the training as realistic as possible. In the Army this means using live ammunition, throwing in surprises, and generally making the situation as confusing as possible.

I believe once our learners in the BE classroom have mastered the basics in the supportive environment of the classroom, it is time to make the training reflect the real world. In group classes, here is where the participants themselves really add to the course. They can ask the tough questions and play the role of difficult people. They can give the pointed criticism needed to make the situation more realistic. As Claire Hart pointed out on her blog, getting the learners out of the class on the factory floor adds needed realism.

In short, we need to prepare them for the battlefield.

5. The After Action Review (AAR)

The final lesson distilled was the importance of the After Action Review. Basically, this was a post training meeting to take stock of our performance and formally acknowledges strengths, areas for improvement, and lessons learned. In the military, we had formal drawn out AARs with written summaries but perhaps more effective were the 5 minutes 'hot wash' AARs. In these short meetings we sat down as a team and discussed the training event with the following agenda.

- Review the training objective

- What was supposed to happen?

- Relavent training resources we used

- What happened? Why?

- What did we do well?

- What do we need better?

- What lessons did we learn?

- Make a plan to improve shortcomings and build upon strengths

In an in-company training environment we need to use AAR like breaks to critically assess our performance. In some courses, this can be done after every lesson. But not all of our participants are going to have such thick skins. As trainers, our job is to effectively observe their performance and offer feedback without hurting any feelings or damaging reputations. This is certainly not easy, but the AAR was the key link between our current skills and future improvement.

Conclusion

I am certainly not advocating that we systematically formalize all of our training and execute it lock-step as we did in the military. Much is to be said for the holistic approach, and such formalized training does not always align with the learners' expectations and desires. Additionally, implementing these methods requires a significant amount of planning and admin time which can eat away at choosing and designing the best activities. However, I feel that as professional in-company trainers, such an approach toward training helps us to ensure that the time spent in class is actually making a positive impact on their job performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment